Past, Present, and Future in New York City

New York is always changing. Is it for better, worse, or something else?

I wish I could say my love for Manhattan is exceptional. I wish I could say it’s different from the millions who lose themselves in the city’s endless urban canyons, swept up in its frenetic pace, and inspired by its culture, architecture, and style. It isn’t. I love New York unabashedly for every cliche reason to love New York.

Joan Didion said it best (of course).

I am not sure it is possible for someone brought up in the East to appreciate entirely what New York, what the idea of New York, means to those of us who came out of the West and the South… New York was no mere city. It was instead an infinitely romantic notion, the mysterious nexus of all love and money and power, the shining and perishable dream itself.

I first went to New York as a seventeen-year-old senior in high school on senior trip with my mom. I remember feeling very brave about the whole thing, which was not a wholly inappropriate emotion, I suppose; New York requires bravery, especially from those geographically unsuited for its splendor, like me. We flew into Newark, took a bus through the Lincoln Tunnel, and spent the next four days walking everywhere. My favorite memories were the unplanned incidents. Descending into an underground Italian restaurant for dinner. Buying a paperback from a street vendor whose books spilled off his pop-up table. These struck me as very New York things to do, even though I only had 48 hours of New York experience to judge by.

After that trip, I told everyone I was going to live in Manhattan (I said I would do grad school there to make it more believable). This turned out be a lie. I never have and likely never will live in Manhattan, though since living in Maryland, it’s been much easier to visit, even with a baby.

The Gentrification of the New York City

With that outsider status fully acknowledged, I carefully tread into what I really want to discuss, namely the changes that New York City, particularly Manhattan, has undertaken in the last several decades.

That New York City has transformed since the 1970s isn’t controversial, nor is the fact that Manhattan morphed from a somewhat dangerous, eclectic, partially industrial town into the milder and wealthier tourist destination it is today. What is debatable is whether that change has been for the worse, for the better, or something in between.

Let’s start with the bad. I recently read a polarizing book by Jeremiah Moss called Vanishing New York. The book moves neighborhood by neighborhood surveying the gentrification that’s completely altered the city’s landscape.

Here is the crux of Moss’s position: New York used to have distinct and interesting neighborhoods that attracted the outcasts of society. These neighborhoods — part punk, queer, industrial, small business-friendly, or all the above — existed in tension with New Yorks's lucrative finance, media, and fashion industries until very distinct policy decisions and marketing transformed New York into a playground for the ultra-wealthy. Along the way, New York lost its soul.

The gentrification process follows a three-part process (I’m attaching dates here pertaining to many neighborhoods in lower Manhattan, though the process happened later in Harlem and even later in Brooklyn and Queens. And it is still happening in other cities around the world).

Part 1: In the 1970s and 80s, seeking space, cheap rents, and acceptance, artists and the LBTQ community moved into Manhattan’s undeveloped residential and industrial neighborhoods. These people were welcome, though unbeknownst to them, they were the first wave of gentrification.

Part 2: Word slowly got out that there was interesting art and lifestyles to be found in these once overlooked neighborhoods. This attracted more people to the area, including those with a little more wealth who wanted a “true” New York experience.

Part 3: As the neighborhood started to see an influx of wealth, the newcomers expected more amenities like better grocery stores, shops, gyms, etc. Landlords, recognizing they could increase rent, pushed out small businesses and mom & pop stores in favor of chains and luxury brands. At the same time, parts of the neighborhood were leveled to build new real estate, particularly upscale apartments. The cycle repeated until the original character of the neighborhood is lost.

In the book, Moss lays a lot of blame on “yuppies”, those wealthy New York transplants who invaded neighborhoods and caused their rapid transformation.

The best and most entertaining part of the book, if only for the sheer absurdity, are the anecdotes about how New York’s past, particularly its grittiness and culture, has been repackaged as consumer experiences for the wealthy. 1 Moss calls this fauxstalgia.

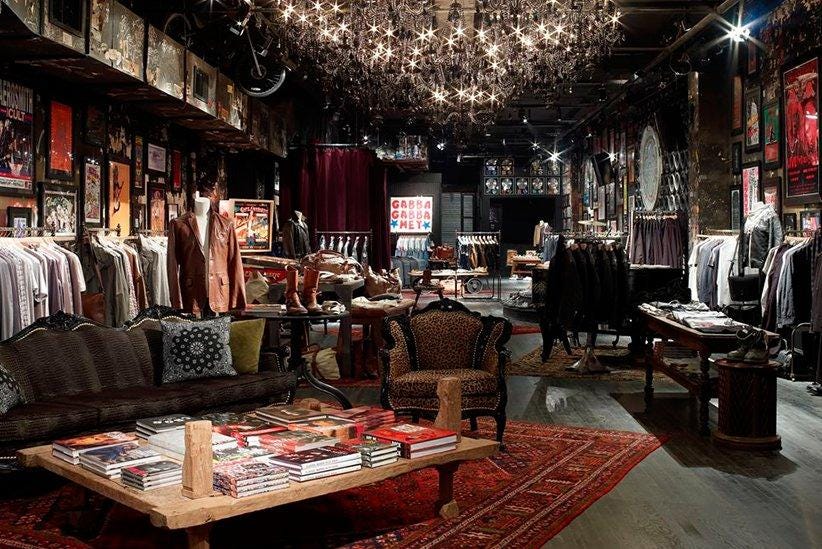

As an example, consider the CBGB music club. In the 70s, it was home to the American Punk scene with bands like the Ramones, Blondie, and the Talking Heads starting out in the dingy, drunken halls. After the club was sued out of existence by an opportunistic landlord, men’s fashion designer John Varvatos opened a store in the space and “preserved” aspects of the punk days like the graffiti behind the toilet and stickers on the wall. Shoppers could come purchase designer clothing but feel punk while they shopped. Several punk icons were even there to help open the store in what many, including protesters, rightfully decried as the complete opposite of punk.

Aside from the yuppies, Moss also presents Michael Bloomberg, the three-term mayor who served from 2002 to 2013, as the main antagonist. Moss shares some of Bloomberg’s most damning quotes in the book.

“We want rich from around this country to move here. We love the rich people.”

“Wouldn’t it be great if we could get all the Russian billionaires to move here?”

“If we could get every billionaire around the world to move here it would be a godsend that would create a much bigger income gap.”

These quotes look a little worse in today’s billionaire-bashing environment, but boy, they weren’t so hot at the time, especially if you happened to like New York just fine the way it was. Bloomberg allowed for unprecedented tax breaks for developers and rezoned and leveled his way through every part of the city.

Moss’s critique is at its strongest when he shares and analyzes these stories. Clearly, New York still has some pride in its rougher history and deliberately uses it to sell a sanitized version of the past feels if not deceptive, at least a little lamentable.

While I don’t mean for this article to be a review of Moss’s book, I do want to briefly share a few more thoughts for the curious few.

I enjoyed the first 150 pages the most. It gets repetitive, especially Moss’s passion, which fills the book with indignation and dread. Though he finally gets to some solutions at the end, it feels like too little and too late.

Sometimes Moss’s nostalgia for dinginess overshadows what’s really been lost or what could actually have been saved. For example, he is sore about the fact that Times Square is no longer a den of prostitution and peep shows. Is that even reasonable?

Moss is nostalgic for a very particular time in New York. But New York’s history extends far beyond 1970. People move, wealth shifts hands, and businesses come and go.

New York of the Present

It’s hard to argue with anything Moss says in terms of the physical changes to the city. You feel this walking around Manhattan. Luxury apartments pop up in unexpected places, the neighborhoods don’t feel as distinct as they perhaps once did, and chain stores and restaurants are everywhere.2 Does this really mean New York has lost its soul?

I don’t think I’m totally qualified to answer that, but speaking strictly as a tourist, definitely not. New York is still an amazing place to visit and has one of the most unique cultures in the country despite the chain stores and gentrified neighborhoods. New York isn’t as suburbanized and bland as Moss would have us think.

For one thing, New York isn’t filled with exclusively wealthy people. The median household income is surprisingly average at about $67,000, a few thousand more than the national average of $64,000. Manhattan’s is higher at $87,000. 3

Lest we take that stat on its own, consider another metric, Per Capita Income, which takes the total income of an area and divides it by the population for an area average. As of 2010, Manhattan had the highest PCI in the country, while also having a 16% poverty rate, 5% higher than the US average.

In other words, New York is a place of extremes with both more millionaires and homeless than any other city in the United States. In between, of course, is a sizable working and middle class.

The second relevant aspect of today’s NYC, something Moss only touches on lightly in his book, is the influx of immigration to the city. Queens, in particular, is one of the most diverse cities in the United States. In the city as a whole, 36% are foreign-born and 48% speak a language other than English at home.

New York of the 1970s was diverse, yes, but nothing compared to today. Whereas New York of the past was colored by societal misfits, today’s New York is enlivened by immigrants. It may not be as radical or punk or queer as it once was, but neither is it taken over by white, suburban culture as Moss imagines. 4

Finally, the largest benefit to New York’s transformation is how safe it has become. The media likes to twist this (especially right-wing media who seem oddly bent on describing New York as a failed hellscape), writing mostly about random acts of violence. While tragic, these events are outliers. Today, New York has a violent crime rate of 538.9 per 100,000 residents (this includes all five boroughs, not just Manhattan). 5 That’s four times less than St. Louis, Baltimore, and Detroit, and right on par with cities like Colorado Springs, CO and Norfolk, VA.

A safe city doesn’t just help the rich. It helps everyone, and since much of the violence was (and is) concentrated around public transportation, a safer New York City actually benefits the working class who commute into the city as much as the wealthy.

New York of the Future

Speculation is always fun, though I’ll admit to not being too well-read in this area yet, and so present just two small observations about where New York is headed.

Remote Work

So far, New Yorkers aren’t going back to work in person. I noticed this on my most recent trip to the city in May. When I’ve visited in the past, it seemed like the city was composed of equal parts tourists to residents/workers. This time, it was overwhelmingly filled with tourists.

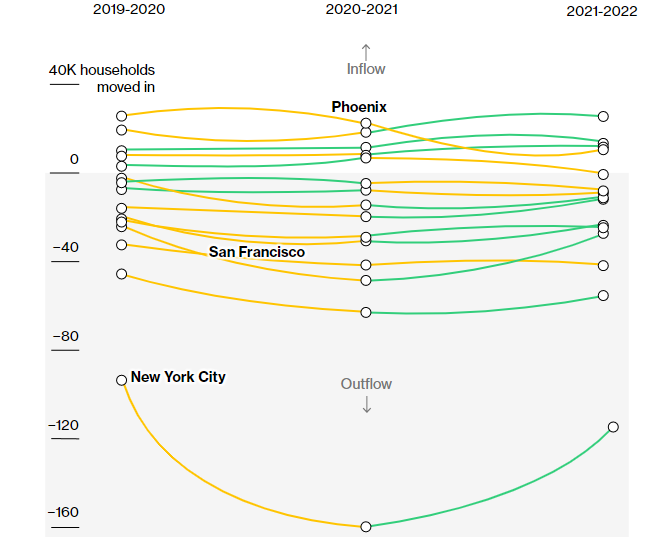

Office occupancies in New York are down 62%. Much fewer people, especially white-collar workers, are coming into New York to work. It also appears that migration out of Manhattan and the other boroughs is continuing. This isn’t unique; New York has been losing residents since 2016. COVID accelerated New York’s outflow, yet the influx, while not yet making up for the loss, is the most rapid of any metropolitan area.

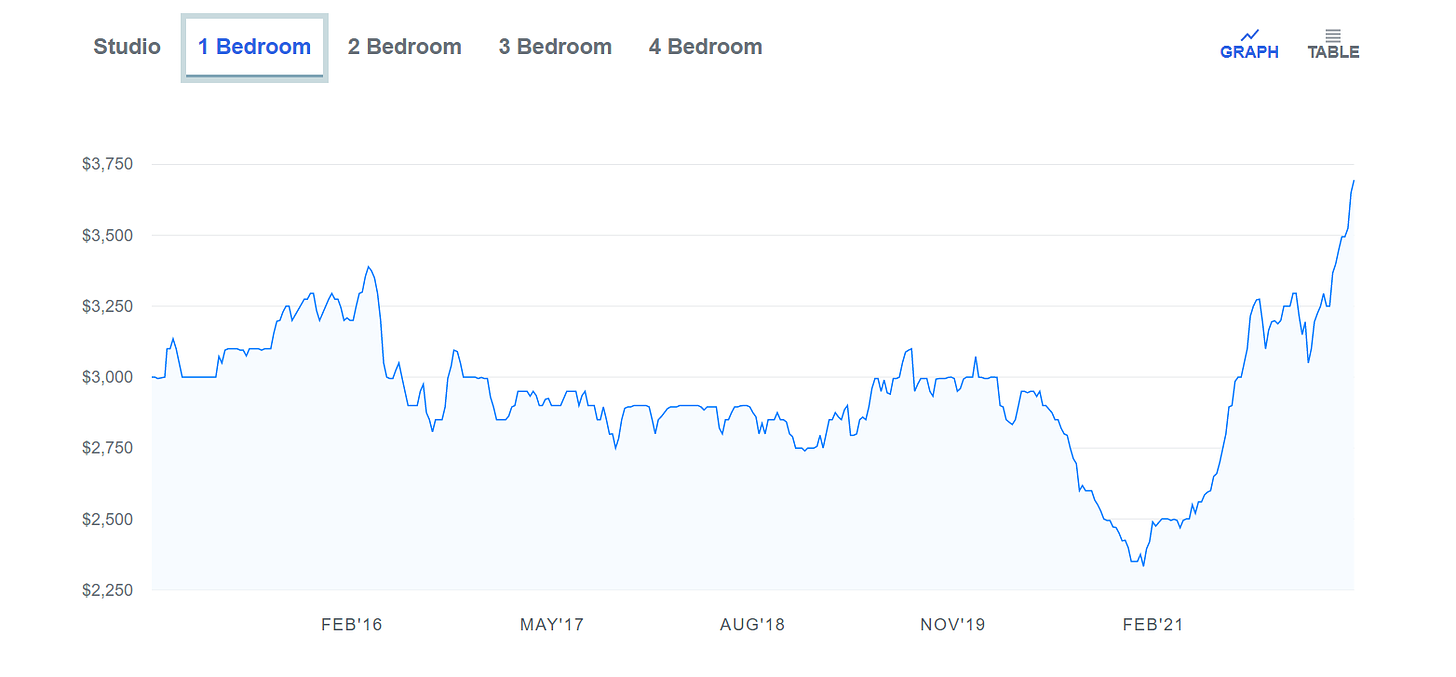

New York has not fully recovered, but what’s curious is that rent is shooting through the roof at the same time. Why is rent so high? Perhaps there’s a greater influx than is accurately accounted for and that competition is increasingly stiff for available units. Perhaps landlords are recognizing the influx and testing out increased rent prices.

If not for work, seems that wealthy white-collar workers are moving to the city not to work, but simply for the lifestyle. Why else would you move to the most expensive place in America? Many people left the city for more space, but a group has moved to the city for the simple fact that New York is still New York. If you’re young, make a great income, and can live anywhere, why not go to New York with thousands of others just like you?

Let’s say this trend continues and New York is filled with young single professionals who don’t actually work in the city. How will that change neighborhoods? Offices? Housing and retail prices? Perhaps it doesn’t change anything except continue to make Manhattan an unaffordable place to live.

Real Estate Recovery

It wasn’t just residents who left during the pandemic; many small businesses closed their doors and never reopened. The map below shows the shuttered storefronts.

Additionally, and as I already discussed, offices are sitting vacant. While residential real estate is red hot, commercial real estate lags behind. I’m a little pessimistic about anyone doing terribly creative things with empty offices. Some may turn into apartments, and while you can imagine a real estate developer trying something crazy — an indoor amusement park, a multi-tiered greenhouse, truly encapsulated living quarters where a single high rise contains housing, gyms, groceries, parks, restaurants, etc. — more likely than not, these buildings will sit empty.

For small businesses, though, this post-pandemic era might be the perfect time to open a new store. As Moss noted in his book, realtors raised prices to attract luxury goods and chain stores. Now, with prices a little lower, an influx of small independently owned stores could open. This would give new life to previously gentrified neighborhoods.

So that’s New York. Ever-changing, always becoming something new as it grapples with changes in wealth, work, and demographics. Our family is currently on a road trip across the US that will last until nearly the end of July. We won’t visit many big cities — in fact, most of the time will be spent in small towns. Next month, I’ll share a recap of our trip and some thoughts on the changes affecting small-town America.

This is not a new occurrence. Marxists critics, particularly Antonio Gramsci, have described how capitalist culture takes fringe ideas and movements, sands off the rough edges, and produce a sanitized version for the masses.

It’s funny to me how many of the same stores exist across Manhattan. For example, you could visit a gigantic Nike store in the Upper East Side, Midtown, Flatiron District, or Soho. Does Manhattan need four Nike stores?

While that is high, it’s nothing like San Francisco and Bay Areas of California, the counties surrounding Washington D.C. or suburban New Jersey where the household income is well over $125,000.

Neither diversity nor a range of incomes necessarily makes New York an interesting place to visit or live. A wealthy American and a wealthy immigrant have more in common than a wealthy American and a poor American.

From 1960 to 1990, roughly two million people left Manhattan due to its high crime.

I've thought a lot about gentrification as a white young professional New Yorker with a household income well above the average you quoted--especially because I believe strong neighborhood communities are the most important social good in America (much more important that some hyper-mythologized "soul" Moss wants to write a city into having). Gentrification breaks those communities apart as few things can. We have to live in the city because a job requires us to--where do we live if we don't want to be part of gentrification? The Upper East side, where the average income is as much above ours as ours is above the city average? I genuinely don't want to break apart communities that have seen Manhattan develop over several decades, but I also need to live somewhere.